But white neighbors resented the resort’s popularity. Tires were slashed. The Ku Klux Klan purportedly set fire to a mattress under the main deck and torched a Black-owned home nearby.

When harassment failed to drive the Bruce’s Beach community out of town, city officials in 1924 condemned the neighborhood and seized more than two dozen properties through eminent domain. The reason, they said, was an urgent need for a public park.

The Bruces sought $70,000 for their two beachfront properties and $50,000 in damages. They received $14,500. The other families, Black and white, received between $1,200 and $4,200 per lot.

For decades, the properties sat empty. The Bruce parcels were transferred to the state in 1948, then to the county in 1995. A county lifeguard center occupies the land today. As for the remaining lots, city officials eventually turned them into a park, worried that family members might sue to regain their land unless it was used for the purpose for which it had been originally taken.

When Hahn realized that the county now owned the land where the Bruce resort once stood, she jumped into action.

She called Anthony Bruce, whose voice still cracks whenever he talks about the city’s actions and how they tore his family apart.

Charles and Willa, his great-great-grandparents, ended up as chefs serving other business owners for the remainder of their lives. His grandfather Bernard, born a few years after the condemnation, was obsessed with what happened and lived his life “extremely angry at the world.” Bruce’s father, tormented by this history, had to leave California.

“I just want justice for my family,” said Bruce, who works as a security supervisor in Florida and teaches English online. He’s the only Bruce today who can manage to talk publicly about the beach — but even he feels worn out. “I’m just looking for hope and mercy.”

Hahn sat down with county lawyers and discussed three possible options:

One, transfer the land back to the Bruce family. Two, transfer the land with a ground lease back to the county to continue the lifeguard operations — and pay fair-market rent to the Bruce family. Three, keep the land but determine the value of the property and make some kind of monetary payment to the Bruce family.

Many details still need to be worked out. Transferring the land from public to private ownership would require state legislation, but numerous legislators have told Hahn that they would introduce the bill. As for the price tag, initial estimates indicate that these options could cost the county $40 million to $70 million.

“At this point, I do not know,” Hahn said. “This all just kept churning in my heart and stomach, and I wanted to keep moving forward … so I’m finding out all this stuff in parallel. Hopefully we’ll have all the facts before us pretty soon, so we can make some good decisions with the family.”

Across the state, leading voices on equity and justice say giving back the land would be groundbreaking. It could also provide guidance on how other cities and states could atone for historically dispossessing certain groups of people from the ability to own property and build wealth.

“The county is taking a monumental step towards progress and considering options that are creative, that seek to define equity in a new way — in a way that could potentially get at the heart of justice beyond a monument,” said Effie Turnbull Sanders, who has worked for more than 20 years in land-use law and currently serves as the California Coastal Commission’s environmental justice commissioner.

State Sen. Steven Bradford (D-Gardena), who was recently appointed to California’s reparations task force, said Bruce’s Beach is a compelling case study for the many issues he’ll be addressing in his new role.

Righting these wrongs won’t always be as clear-cut as giving back the land or even monetary payment, he said, but resetting the playing field can come in various forms. Could the descendants of those who were enslaved, for example, be provided a free education at the University of California? Could those historically denied home ownership be somehow enrolled in a first-time home buyers program that doesn’t require a down payment?

As for those who question why people today are on the hook for paying for past injustices:

“If you can inherit generational wealth, you can inherit generational debt,” Bradford said. “That’s debt that Manhattan Beach owes to the Bruce family. It’s debt that California and this nation owes to many more families like the Bruces.”

Back in Manhattan Beach, city leaders have made clear that financial reparations should not be the town’s responsibility, and residents have been at odds over whether to even apologize.

“I do not want an apology, and I don’t think you do either,” Hadley, the mayor, told a virtual meeting room filled with more than 300 people. Many had expressed concern that an apology would expose the city to potential lawsuits.

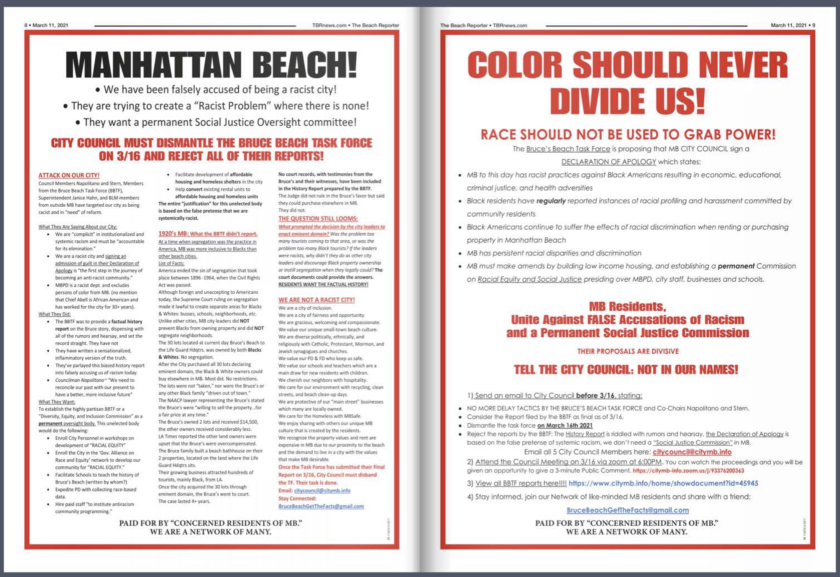

The issue continues to divide this affluent town of 35,000. Social media tirades have become the norm, and a two-full-page advertisement in the local newspaper, paid for by “concerned residents of MB,” called on residents to “unite against FALSE accusations of racism.”

Longtime community leaders have also questioned how much generational wealth was actually lost: Would the Bruce resort, they said, have survived the Great Depression, World War II and other major economic disruptions?

After hours of deliberation and public testimonies, the city council agreed this month to maintain a website on the history of Bruce’s Beach and commissioned two new plaques to acknowledge the past. The council also allocated $350,000 to be spent on an art installation, but it postponed voting on whether to issue an apology.

And to the dismay of those who had urged the city to go beyond measures that are symbolic at best, the city council disbanded a task force of 13 volunteers who had spent hundreds of hours researching the history, drafting an apology and recommending ways to help the community move forward in a more just and equitable way.

Kavon Ward, who started the grass-roots movement Justice for Bruce’s Beach, said she has increasingly felt threatened living in this city. The few people in town trying to speak up have been silenced, she said. So many of her neighbors continue to “live in a bubble of white supremacy and white fragility.”

“These residents of Manhattan Beach care more about money than doing what’s right,” said Ward, who has more than 7,700 people supporting her petition for the city to pay restitution to the Bruces for 95 years of lost revenue. “You would think that Janice Hahn, moving in the direction that she’s moving in, would be some source of inspiration to Manhattan Beach — but clearly it isn’t.”

Duane Shepard Sr., a 63-year resident of South L.A. and designated Bruce family representative, said the city doesn’t get a pass just because the county is now trying to give back the land.

“Manhattan Beach needs to wake up. The world is watching,” he said. “They’re in the crosshairs of everybody right now.”