This blog was written by former intern Joseph DeMartin

On March 24, 2025, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in a case called Louisiana v. Callais. The case carries massive implications for voting rights and democracy, as it involves two related but distinct concepts: racial vote dilution and racial gerrymandering.

The easiest way to separate these two ideas is to examine the winding path Callais took to end up at the Supreme Court.

,

Stay Updated

Keep up with voting rights news. Receive emails to your inbox!

,

Claim of Racial Vote Dilution

Following the 2020 census, Louisiana drew a congressional map with six districts. Black voters made up a majority in only one of those districts, even though a third of Louisiana’s voters are Black. Black voters in Louisiana brought a claim arguing that this map violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA), as explained below.

“Cracking,” “Packing,” and Section 2 of the VRA

Section 2 of the VRA forbids any state or locality from using any “standard, practice, or procedure” that “results in a denial or abridgment of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.” In other words, it says that suppressing a person’s rights because of their race is illegal. Importantly, Section 2 does not care about the intent of the standards, policies, or procedures in question; it only focuses on their impact.

Section 2 also considers whether, under the challenged law, voters of color have the opportunity “to elect representatives of their choice.” Because it focuses on impact rather than discriminatory intent, Section 2 is a powerful tool for voters and voting rights organizations to seek relief from discriminatory, anti-voter legislation.

,

,

Throughout history, many states and localities have used redistricting, or the drawing of congressional maps based on local populations, to weaken the power of voters of color. They’ve done so by, for example, “cracking” Black populations between multiple districts to reduce their voting power or “packing” them into a smaller number of districts to reduce their representation. To avoid diluting votes and violating Section 2, states and localities must draw “Section 2 districts,” where voters of color can elect their chosen candidates under certain circumstances.

In a case called Thornburg v. Gingles, and in subsequent cases, the Supreme Court set forth a test to determine when drawing a Section 2 district is required. First, three preconditions must be met:

- Minority voters must comprise a large enough percentage of eligible voters (of the voting age population), and they must live close enough together to form a majority in a compact district;

- The minority voters in the challenged area must vote in a politically cohesive manner, that is, they vote together as a bloc for candidates; and

- White voters in the majority must vote in a politically cohesive manner, ensuring the candidate preferred by the minority voters consistently loses elections.

Together, the last two preconditions are referred to as “racially polarized voting.”

,

,

If plaintiffs can prove the above preconditions, they must prove that the “totality of the circumstances” demonstrates that minority voters have had less opportunity to participate in the electoral process and are prevented from electing the candidate of their choice. To support this analysis, plaintiffs look to the “Senate Factors,” as described in a report added to the 1982 amendments to the Voting Rights Act. Some of those factors include:

- The history of official discrimination affecting the voting rights of people of color;

- The degree of racial polarization in voting;

- The presence of discrimination against people of color in the education, employment, and health;

- The presence of overt or subtle racial appeals in political campaigns; and

- How often candidates of color have won elections.

Not all or even a majority of the Senate Factors must be proven to satisfy this part of the test. The factors are meant to outline a flexible standard that accounts for relevant evidence of social and historical conditions that lead to discrimination against voters of color.

,

,

If a state or locality fails to draw a Section 2 district when the Gingles conditions are met and the Senate Factors are satisfied, it has engaged in vote dilution.

Section 2 and Louisiana’s Map

In March of 2022, Black voters and civil rights groups sued, challenging Louisiana’s map and accusing the legislature of diluting Black votes by drawing just one majority-Black district. A district court in Louisiana ruled that this map violated Section 2 because the Black voting-age population was sufficiently large and compact enough to require two majority-Black districts. The map was, in this sense, an example of “packing.”

,

,

The court also found racially polarized voting and that the plaintiffs satisfied the totality of the circumstances test. The court told the Louisiana legislature to return to the drawing board and create a new map with two majority-Black districts for the 2024 congressional election.

Claim of Racial Gerrymandering

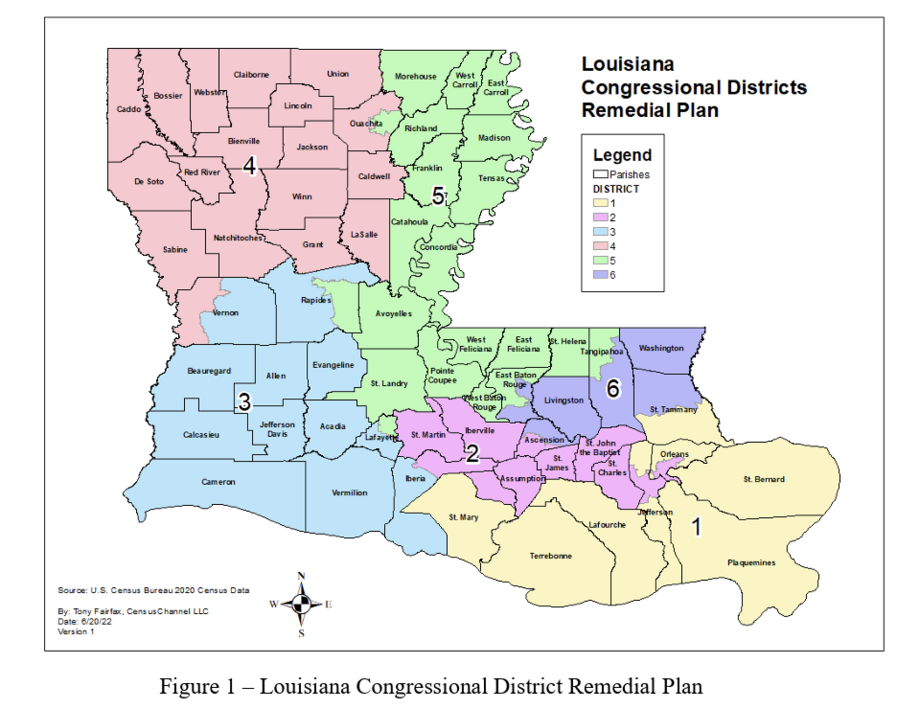

So, Louisiana went back and drew a new Section 2-compliant map. But there was only one problem. The map that the plaintiffs and the district court wanted Louisiana to implement looked something like the image below.

,

,

In this map, all the districts are compact and regularly shaped, and districts 2 and 5 (the pink and green districts) are majority-Black districts, in compliance with the VRA.

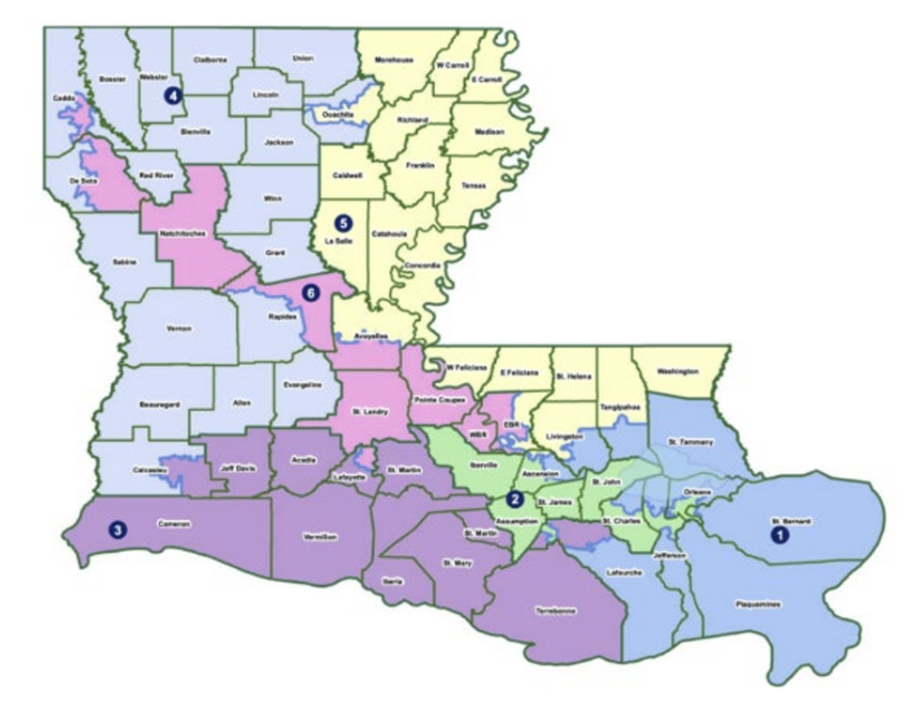

However, Louisiana chose to enact maps that looked like the below.

,

,

In this map, districts 2 and 6 (the lime green and pink districts) are majority Black districts. But district 6 is not compact; it stretches from Shreveport in the Northwest of the state to Baton Rouge in the center.

This oddly shaped district 6 prompted 12 “non-African American” voters to sue in a different court altogether, accusing Louisiana of discriminating against them by racially gerrymandering the new map. But how can Section 2-compliant maps be racially gerrymandered if they are meant to give voters of color more access to the political process?

Racial Gerrymandering and the Fourteenth Amendment

A racial gerrymandering claim comes under the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, which states, “[n]o State shall...deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” The Equal Protection Clause prevents governments from discriminating against different classes of people. Yet, unlike Section 2, the Fourteenth Amendment requires proof of intent to racially discriminate.

,

,

If a court decides that a law is intended to classify voters based on race (or religion or national origin), the court will subject the law to the highest level of legal review, called “strict scrutiny.” If a court decides that there was a different intended classification, like gender or income level, it will apply a lower level of scrutiny, either “intermediate scrutiny” or “rational basis.” To determine the level of scrutiny, we have to understand the intent — why the legislature drew the lines.

If race is the primary factor for placing voters in or out of a district, the Court subjects the map to strict scrutiny. And when a court applies strict scrutiny, the government action must be narrowly tailored to serve a compelling government interest. In other words, a state cannot use race as the main way it decides to redistrict unless it has a powerful reason.

The 12 “non-African American” Louisiana voters argue that the state’s new map primarily used race to pack Black voters into the strangely shaped 6th district. The “non-African American” voters argue that Louisiana engaged in discrimination against them by drawing districts based on race and providing Black voters the opportunity to elect candidates of their choosing. According to this argument, because race was the primary factor in redistricting, strict scrutiny should apply, and the Court should strike down the maps.

,

,

In response, Louisiana makes two arguments. First, District 6 is shaped oddly because it is designed to protect two influential Republican incumbent Congressmen, Steve Scalise and Mike Johnson. If politics were the primary motivation for shaping the lines, then rational basis (not strict scrutiny) would apply, and the government would receive greater deference.

Second, even if strict scrutiny applied, Louisiana argues that it had a compelling reason to draw the new maps based on race. In a 2017 case called Cooper v. Harris, the Supreme Court affirmed that complying with the VRA is a compelling reason to use race as the top factor in redistricting. Using that case, Louisiana has “good reasons” for drawing their maps based on race — namely, that a federal court told them their original maps were likely a violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

What’s at Stake in Louisiana v. Callais

Herein lies the tension for voting rights advocates: Louisiana must consider race to draw Section 2-compliant district lines and give voters of color equal access to the political process. But does that mean race is always the guiding factor when drawing a Section 2 district? If the Supreme Court answers yes to this question, it would have to apply strict scrutiny to all Section 2 districts, and remedial maps would become much harder to make.

,

,

Furthermore, if strict scrutiny were applied to all Section 2 districts, would complying with the VRA satisfy the “compelling government interest” requirement? The Supreme Court has not shied away from substantially weakening the VRA. Shelby County removed the guardrails of Section 5 preclearance. Brnovich made non-redistricting Section 2 vote denial claims far more difficult.

If the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the “non-African American” voters, states would have far more difficulty creating Section 2 districts without running afoul of the 14th Amendment. States could more easily silence the voices of voters of color. Using the 14th Amendment to strip Black voters of political power is fundamentally backwards and at odds with its original purpose.

It is vital that the Supreme Court preserves these safeguards for voters of color and upholds its precedent protecting Section 2 vote dilution claims because the fight for fair representation goes beyond lines on a map. It’s about realizing a vision of an equitable democracy where all people have power and all people have a voice. For decades, voters of color have had their power and their voice threatened. It’s time to put an end to it.

You can join the fight for fair maps by joining your state or local League of Women Voters. Learn more about how to use the law to advocate for equal representation. Learn what your local redistricting process looks like and attend public hearings. Share what you learn with your friends. And be part of the movement for a democracy that truly reflects its voters.